IA Insights > Blog

Did You Write That Down?

In 2009, Atul Gawande published the fascinating book The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, in which he describes the simple idea of a written checklist. Though know-how and sophistication have increased, we often fail to deliver results—primarily due to an overwhelming amount of information and complexity. Intriguing stories abound: how skyscrapers are built, how Johns Hopkins Hospital reduced hospital infections, how airline pilots prepare and execute a flight, and how a James Beard Award-winning chef runs her restaurant. The unifying factor in all these cases? A simple checklist. Simple, brief, and to the point, Gawande concludes that checklists help with memory recall, set the minimum number of steps, and ultimately establish a higher standard of performance. There is extreme value in writing things down.

Every day in the United States, millions of meetings are held across a variety of mediums, industries, and topics. Within each of these meetings, similar challenges exist: attendees arriving late or leaving early, undefined meeting objectives, poor listening, vague decision-making, and lack of next step actions. In this continuation of our blog series around Taming the Online Meeting Monster, I’ll expand on the perennial challenge and impact of nonexistent meeting notes and unclear next steps. I’ll then offer a few practical tips and tools on how you can tame these monstrous behaviors and get your meetings—and ultimately your results—back on track.

As you reflect on meetings you’ve attended within the last month, how many of these situations sound familiar?

- One person keeps reminding the group over and over about a pet peeve.

- The group spins its wheels, covering the same topic repeatedly.

- So much information is discussed that you become overwhelmed, confused, or think, “what are we talking about? Where are we?”

- You leave the meeting unclear about key decisions and what to do.

The connection between these common situations is an underlying deficiency—the absence of someone capturing key ideas in real time in front of the group. For a group to be effective, they need a shared group memory*. In formal meetings, such as board meetings, the concept and practice of “meeting minutes” can serve this purpose. However, these minutes represent the memory of one individual, and the record is often not available to the group until the next meeting.

More frequently in meetings today, participants take private notes for themselves. However, this too has inherent challenges as there is no accepted or centralized record of what happened, of decisions made, or of next step agreements. People therefore often arrive to the next meeting unclear about who was supposed to do what.

I recently conducted an engagement for a prominent healthcare company around online meeting skills. At the beginning of the training, I asked the question: “in what percentage of your meetings are notes taken?” The responses I received ranged from 10% to 70%, with a majority saying they frequently leave meetings with unclear next steps.

Do you recall the fictional character Ellen, from our Introduction to the Online Meeting Monster post? Ellen never wants to be at the meeting; she is supposed to be documenting agreements and next steps but instead spends the time reading other emails, checking text messages, and shopping online. We’ve all experienced an Ellen before. So how can you as a leader tackle this challenging behavior?

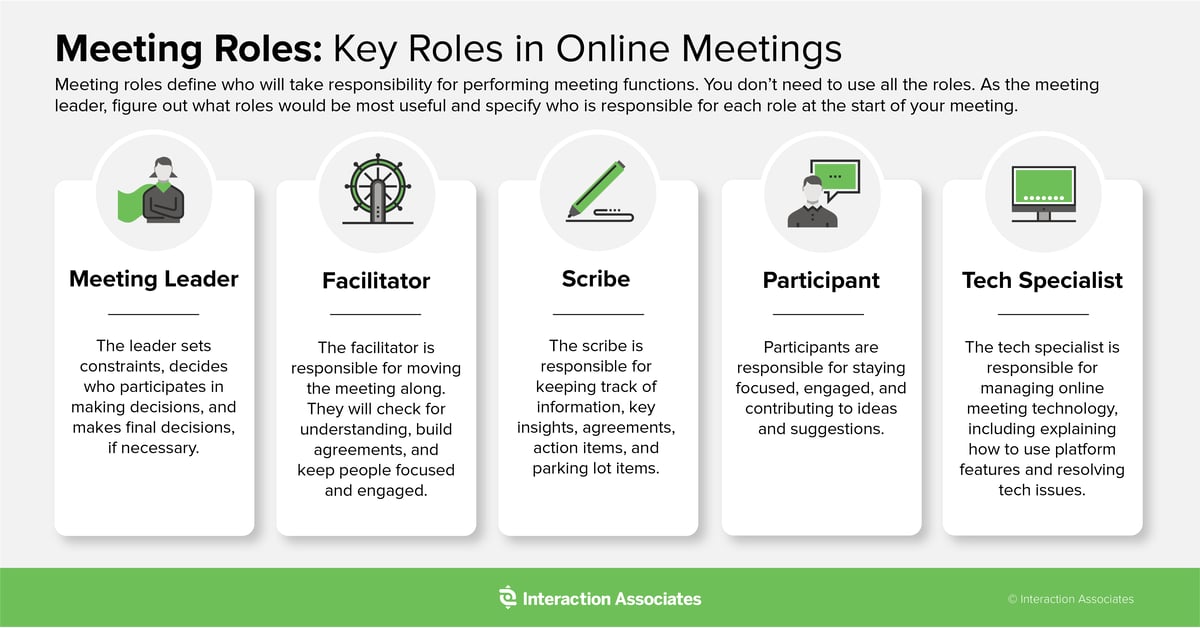

- Assign Ellen the role of “Scribe” by deploying The Interaction Method™. The Interaction Method™ is an approach for working better together and is designed to accomplish tasks and produce results. Specifically, it’s a facilitated approach for building understanding and agreement among people so they can take informed, concerted action. At the core of the Method is “Shared Responsibility for Success,” the principle that everyone in a meeting can play an active and positive role in producing meaningful results.

One of the core elements of activating this principle is to clarify and designate up to five distinct meeting roles that define who will take responsibility for performing a particular function:

By giving Ellen this role, she understands that she is performing a vital part in the group’s success by being the sole person responsible for everyone’s record of the meeting. By officially conveying this role and building an agreement on her level of responsibility, Ellen is now accountable to the broader group.

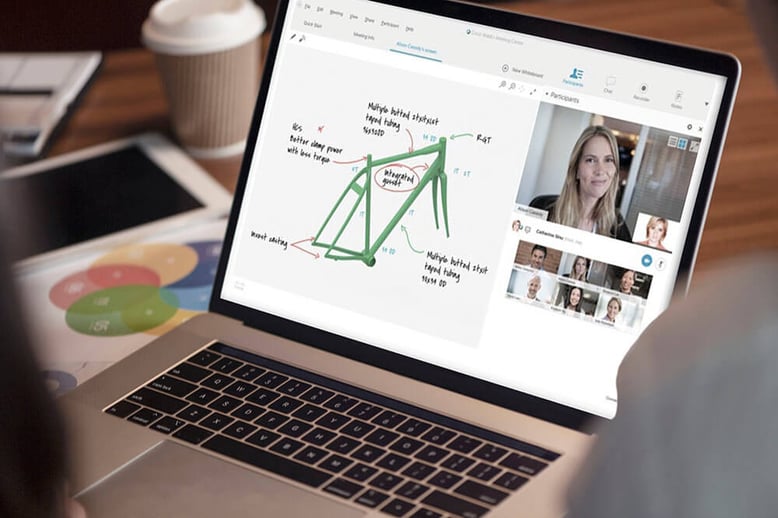

- Use a common visual workspace. In meetings, particularly online meetings, it’s easy for attendees to get distracted. An incoming text message, something interesting just happened outside, or daydreaming about what to have for lunch. We’ve all been there.

Provide focus for the group by using a common visual workspace—a centralized place where meeting attendees can focus their attention. The person presenting information can quickly share their screen so attendees can follow along visually.

When it comes to generating ideas or confirming next steps, it’s helpful for the Scribe to share their notes on screen in real time, so attendees can view the information being captured and comment if a point is summarized incorrectly or is missing.

- Reserve the last five minutes of the meeting to confirm key decisions and action items. Often our meetings can be so jam-packed with content that we don’t allocate time to slow down the process and confirm key decisions and actions before we exit. A simple and effective technique is to take a few minutes at the end of the meeting to review these key decisions and next steps. This helps to promote understanding, clarity, and agreement and can propel crucial action. Stay tuned for our next installment where we cover this practice in more detail.

What’s at play in these closing meeting moments are often the critical link between what Georgetown University computer science professor Cal Newport calls, “shallow work” and “deep work.” It’s my belief that these logistical moments are key to ensuring the team is set up for success to do the deep work— focusing without distraction on critical actions that move the organization forward. The meeting is simply a framework and connective tissue for linking all the deep work that people are doing, allowing for key decisions to be made, solving problems, building the team, and celebrating success in a live environment.

In the coming weeks we’ll be sharing valuable insights from our State of Online Meetings report, which will provide a glimpse into where the Meeting Monster most frequently lurks. In the meantime, if your organization is experiencing symptoms of the Meeting Monster, check out our upcoming live-online events.

Did you miss a blog in the Tame the Online Meeting Monster™ series? Find the published blogs below:

Part 1: Meet the Online Meeting Monster™

This blog will introduce the monster and highlight key areas to look out for in your online meeting. We’ll be tackling each topic in the coming weeks.

Part 2: Why Are We Meeting?

Start your meeting off on the right foot by preparing yourself and attendees. In this blog we will provide you the tools to do this seamlessly.

Part 3: Is Anybody Listening?

Online meetings tend to have a lot of dead air and blank stares. In this blog we discuss how to overcome this common issue by keeping attendees engaged.

Part 5: Are We Done with This Meeting?

Tired of ending meetings more confused than when you started? Learn three simple practices that will help you end your meetings feeling confident.

*The concept of group memory is outlined by our founder, David Straus, in his book How to Make Meetings Work.

About Chris Williams

Chris’ experience includes work in operations, recruiting, and complex research. He has supported senior-level executives in a variety of industries including economic development, government contracting, and strategy consulting. Chris holds a BA in Political Science from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a Masters in Public Administration (MPA) from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington.