IA Insights > Blog

Abraham Lincoln and the Collaborative Leader's Dilemma

Abraham Lincoln and the Collaborative Leader's Dilemma

When circumstances call for bold, decisive action, collaborative leaders face a dilemma. How do they get the right amount of buy-in without losing the window of opportunity or, worse, giving an imminent threat a chance to do major damage? Anyone who has held an executive position in a collaborative organization is familiar with this conundrum.

Unilateral decision-making in collaborative cultures runs counter to the expectation that all stakeholders will be consulted and heard. For younger employees who expect managerial transparency and process inclusion, leaders who take unilateral action are inherently suspect.

The purpose of this blog is to address the challenge of balancing inclusiveness with decisiveness. I’ll use Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation—a familiar case for many readers—to illustrate a few guidelines for addressing this dilemma.

When Lincoln took office on March 4th, 1861, the United States was being torn apart by divided loyalties and the prospect of civil war. Between Lincoln’s election and his inauguration, seven southern states passed resolutions to secede from the union, formed a new confederation, and established a government with its own constitution and president. Six weeks later, on April 13th, the Civil War between the northern and southern states began.

While the southern states argued that states’ rights and autonomy were at issue, the source of the controversy was the institution and practice of slavery. Lincoln’s own Republican Party was polarized over the proper response to this existential threat to their young nation. On the Union (northern) side, there were two major camps: conciliators and hardliners. Conciliators wanted to compromise with the rebellious Confederacy, hoping to coax slaveholding states to stay in or return to the Union. Hardliners, outraged at the perceived treachery and at slavery itself, pressed for swift and lethal punishment. Lincoln, a lawyer guided by rules of law and considered debate, and now a reluctant war president, was faced with situations that demanded clear and decisive action.

Lincoln’s response was paradoxical: he patiently assembled a most unlikely cabinet. Doris Kearns Goodwin in Team of Rivals wrote that Lincoln appointed men who represented every faction of his fractious Republican Party. They were independent, strong-willed, articulate politicians and power brokers. Most of them were better educated and more popular than the president himself. From this “quilt of many colors,” Lincoln fashioned an approach that stands, to this day, as a leadership model that’s both collaborative and decisive.

By the summer of 1862, the American Civil War had evolved from a few bloody battles to a series of grueling, family-dividing, deadly, and economically punishing campaigns involving hundreds of thousands of soldiers and support personnel. Lincoln’s cabinet was divided about the right approach to the war effort—negotiate or press on.

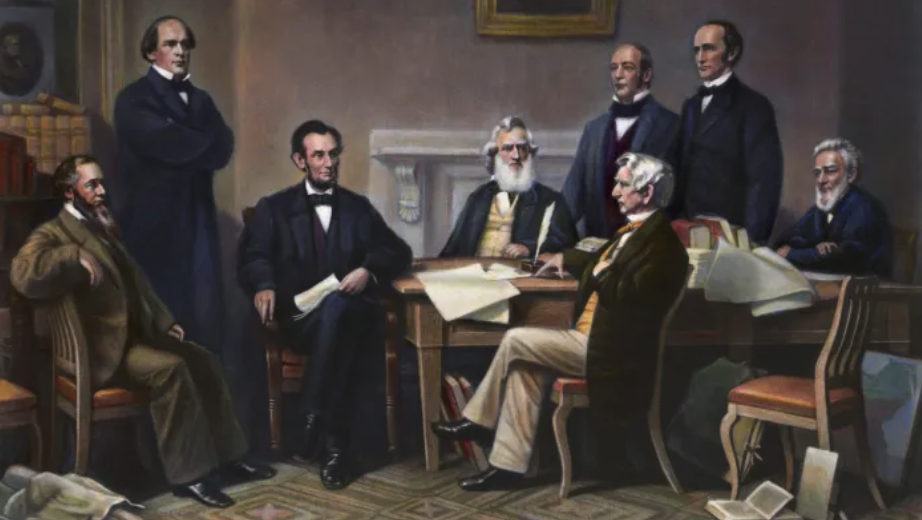

Lincoln made his intentions clear. While he honored the experience and valued the opinions of his cabinet members, Lincoln “wished it to be understood that the question was settled in his own mind” and that “the responsibility of the measure was his.”

Abraham Lincoln reading the Emancipation Proclamation before his cabinet. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Abraham Lincoln reading the Emancipation Proclamation before his cabinet. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

In her most recent best seller, Leadership in Turbulent Times, Goodwin articulates the following set of rules to guide transformational leaders when circumstances require bold, unilateral action:

- Acknowledge when the status quo has failed and a change in direction is required.

- Gather first-hand information; ask lots of questions.

- Find time and space for reflection.

- Exhaust all possible alternatives before going “decide and announce.”

- Anticipate resistance and the content of each viewpoint.

- Assume full responsibility for the pivotal decision.

- Pay attention to the emotional needs of each stakeholder.

- Do not let past resentments fester; no personal vendettas.

- Set high standards of mutual respect and dignity; control anger.

- Give away credit; take the blame.

- Maintain perspective in the face of both accolades and abuse.

- Find ways to cope with pressure, maintain balance, replenish energy.

- Know when to hold back, when to move forward.

- Be accessible, easy to approach.

- Put ambition for the collective interest over self-interest.

- Keep your word.

- Keep your word.

- Keep your word.

On September 22, 1862, after a Union victory at Antietam, President Abraham Lincoln issued a warning to dissenters, “That on the first day of January . . . all persons held as slaves . . . [in rebellious states] . . . shall be then, and thenceforward, and forever free.” On January 1, 1863, as the war waged on, his decree became an executive order which we now recognize as the Emancipation Proclamation.

The Emancipation Proclamation was Lincoln’s decisive statement of strategy. He made the decision himself, but had garnered the full support of his diverse cabinet. The Union would continue the fight until the Confederacy was completely and irreparably defeated and the practice of slavery abolished from the land.

Interaction Associates has been helping people work better together for over 50 years. Learn more about the solutions we offer that have helped transform the way organizations collaborate around the world.

Sources:

https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/emancipation-proclamation/transcript.html